In my recent posts, I have explored the possibility of professional development for GR supervisors. In fact, exploring it so well, I’ve written a course proposal to deliver online training for GR supervisors, incorporating discussion groups, reflection and engagement with the literature in a heutagogical approach.

https://spark.adobe.com/page/ZnNZ3V7gn2RsR/

Reflections and black holes

As I’ve been thinking more about this, I’ve been reflecting on my own supervisory holes, and one that keeps on raising its ugly head is that I don’t know how to help my students with their writing. Writing is commonly given as the biggest challenge that my students face. They hate writing, hate sharing drafts and hate reading the feedback. To be honest, I’ve hated reading and giving feedback and wondered how we can be at such a mismatch.

Formally writing formal writing

Last year (oh horrible year of the pandemic and Melbourne lockdowns), I decided to start an informal writing course for my students and ran a 6 week (then 7, then 8 week) weekly get together to discuss elements of a paper and writing. We covered some weekly topics below- and I’ve started up again this year with a new one ‘titles’.

- Writing, why do we love it or hate it?

- Abstracts

- Literature reviews- how to map the gap

- Effective literature reviews

- Writing methodology and result sections

- Conclusions

- Editing and proofreading

- Figures and tables

How did I run this course and find all these materials? Simple; I followed someone awesome on Twitter (@WriteThatPhD; thanks Dr Mel!), and copied some exemplars, and followed the links to some papers. There is a good example below- a nice link to an article, a well regarded journal article, and a line-by-line examination of the structure. A nice hook we saw in lots of abstracts is the ‘here we show…’ section, straight after the knowledge gap. General feedback from students ‘super helpful’, ‘helps me with my writing’, ‘love the structure’.

I’ve expanded my horizons (and google searches) and have come across a Coursera offering ‘Writing in the Sciences’. I’ve done the first week already (along with 224, 598 others), and find the material very useful. I’m not sure whether to direct my students to this course, or to use this material thoughtfully when giving feedback!

But what does this mean for my professional development?

This is important and underpins my theorising on encouraging academics to be continually learning and upgrading practice and reflecting on the process.

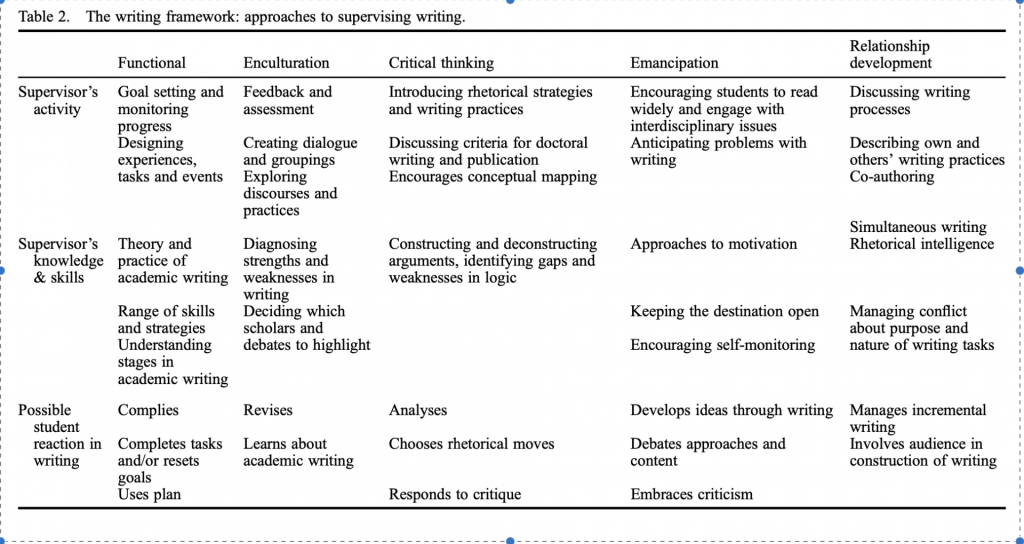

In reality, I have found an example of ‘enculturation’ and I’m using skills in exemplar management to display how ‘things are done’ in science (Lee et al, 2007). I’m encouraging my students to become members of a disciplinary community and I’m reinforcing ‘critical thinking’ skills by analysing texts and helps ’emancipation’ by debating approaches and content.

I’m moving through a form of adult learning, which Mezirow (1991) refers to

moves the individual towards a more inclusive, differentiated permeable (open to other points of view), and integrated meaning perspective

Mezirow (1991) p. 7

Surely a good thing. And while I can start to chart these circles of reflection, practice and change myself, the challenge is to help my GR students understand that this is happening to them, as an intentional or unintentional, consequence of their graduate studies (Stevens-Long et al 2012). Perhaps the heutagogical framework I have investigated needs to be thought of in the context of transformational learning. Once more into the literature I go…

References

Lee, A. (2007). Developing effective supervisors: Concepts of research supervision. Information Services, 21. https://doi.org/10.4314/sajhe.v21i4.25690

Lee, A., & Murray, R. (2015). Supervising writing: Helping postgraduate students develop as researchers. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 52(5), 558–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2013.866329

Mezirow, J. (1991). Transformative dimensions of adult learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Stevens-Long, J., A. Schapiro, A., and McClintock, C. (2012). Passionate Scholars: Transformative Learning in Doctoral Education. Adult Education Quarterly, 62, 180.